by Edward van Voolen (zur deutschen Zusammenfassung) (Heft 15/1)

Does Jewish architecture exist? Is architecture capable help shape Jewish identity in the diaspora (outside Israel)? Looking at the modern Jewish museums, schools and synagogues, the answer seems to be: yes! The decision to erect such buildings has everything to do with a long-term perspective—the ability to say, “we live here”—which in Jewish history was always associated with the decision to remain in the diaspora.

Searching

In Elkins Park/USA the Beth Sholom Synagogue (1959) was designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright (Bild/Titelmotiv: Smallbones, CC0 1.0)

Until recently, the synagogue was the public marker of Jewish identity. Now, more Jews visit a museum than a synagogue. Just as the museum has become the cathedral of the twentieth century for the gentiles, Jews have made the museum their synagogue. Building for Jewish institutions means building for Jewish identity. The fact that well-known architects realise projects at prominent spots in the cityscape, is a clear indication of the new Jewish self-awareness.

In the United States this renaissance took place in the fifties and sixties of the last century. Currently, the accent in American synagogue architecture lies on multifunctional and flexible use of the available space, and in particular on more intimacy. In secularised Israel, the urban synagogue is much less of a community centre and consequently less prominent than in the Diaspora. Only at University campuses it fulfills the role of a landmark.

USA

In the USA survivors of the Shoah and their descendants founded Holocaust museums. The most prominent examples are the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D. C. (1986-93) and the Museum of Jewish Heritage-A Living Memorial to the Holocaust in New York (1997). Less known is Ralph Appelbaum’s Holocaust Museum Houston (1993-96). They all demonstrate the connection American Jews feel to European history.

One example of a modern synagogue is Will Bruders Temple Kol Ami in Scottsdale, Arizona (1992-94, 2002/03). It is a walled ensemble, a habitation in the desert that like Masada or Jerusalem offers a safe haven for Jews living far away from the land of their origins. The complex radiates both a cozy domesticity and a sense of confidence – a Jewish outpost forging a link between the original home in Israel and the current home in the Diaspora.

Israel

In the double synagogue in Tel Aviv the foyer is a meeting point for orthodox and modern-religious or secular Jews (Bild: מיכאלי, CC BY SA 3.0)

In Israel, a building style has developed since the beginning of the twentieth century that adopted not only international modernism but also elements of Mediterranean and local architectural traditions. In Tel Aviv the Swiss architect Mario Botta designed a double synagogue with two cylindrical towers, for Orthodox and for Reform services. His Cymbalista Synagogue and Jewish Heritage Center (1996-98) has to be mentioned in the same breath as Beth Sholom Synagogue in Elkins Park (1953-59) by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Israel’s national Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem, inaugurated in 1953, commissioned Moshe Safdie to add the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in Jerusalem (1997-2005) to the complex on Jerusalem’s Mount of Remembrance. Safdie’s 175-metre long, 16-metre high triangular wedge presents an overwhelming impression. Inside the museum it is appropriately dark. A narrow strip of light at the top of the triangle above shows the bright blue sky. At the exit, the building opens like a funnel onto the surrounding landscape.

Museums

At the end of World War II, Jewish culture had been largely destroyed in Europe. In the 1980’s the immigration of Russian Jews into Germany led to a radical change. It was initially buildings for Jewish and Holocaust museums that gave expression to an altered Jewish self-awareness. At first, existing buildings were converted into Jewish Museums, as the Rothschild palace in Frankfurt/Main (1988), the first major Jewish museum in postwar Germany. They manifested architectural significance mainly in the interiors of the structures.

But by the time Daniel Libeskind came to design the Jewish Museum Berlin (1989-99), things had changed. The external form resembles a bolt of lightning. The inner structure with its axes and the so-called ‘voids’ symbolizes the space left by the Jews who were exiled or killed under the NS regime. Already before the new permanent display opened in 2001, the Museum has become one of the most successful cultural sites in Berlin.

Jewish Community Centers

The Jewish Cultural Center in Duisburg: due to the architect Zvi Hecker, the five “fingers” symbolize the five phases of German history: Roman antiquity, Middle Ages, Weimar Republic to Holocaust and postwar reconstruction (Bild: Nomo)

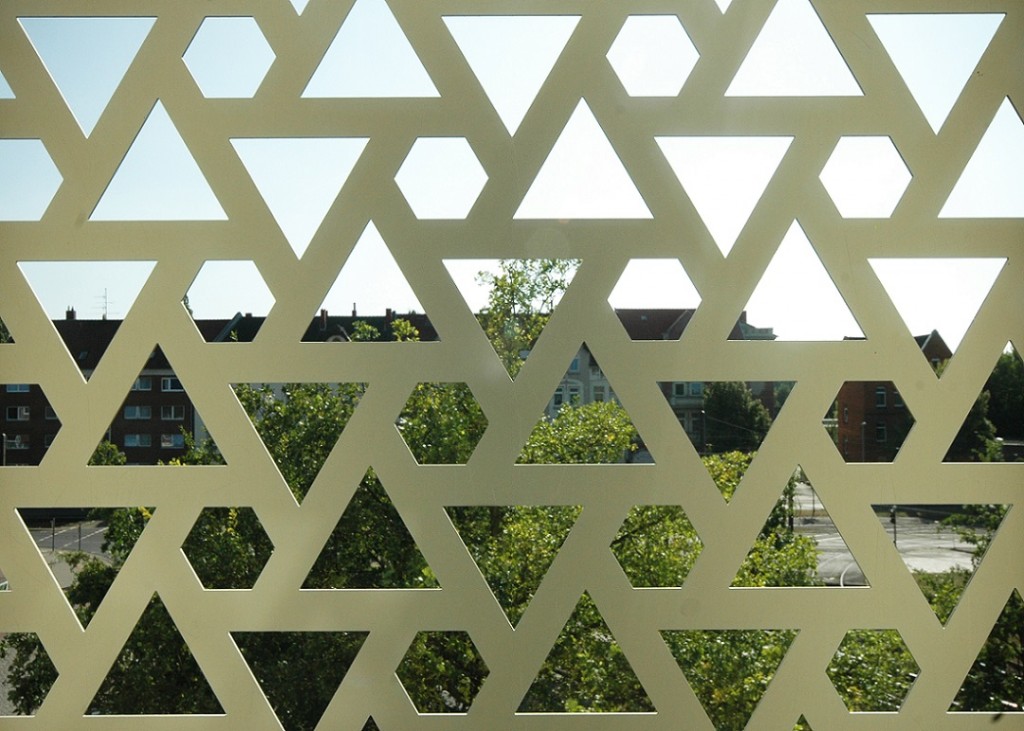

Equally, synagogues and schools now assert a more pronounced architectonic character in the European Diaspora. In Duisburg Zvi Hecker designed the Jewish Cultural Center (1996-99) as a fan-shaped building. Its five sections refer both to the Five Books of Moses (Torah) and the five fingers of an open hand. This striking building radiates a sense of confidence, opening out to the world arround.

In Berlin Hecker had designed the Heinz-Galinski School (1990-95). This plan combines the form of a sunflower with pages of a book. The Hebrew word for book—sefer—is the basis of the Hebrew word for school: beth ha-sefer, house of the book. For Jewish people, who for centuries had no country of their own, the book was the most important possession. From a central courtyard the building fans out, like petals or pages flying off into the wind.

The architect Adolf Krischanitz, working in a minimalist style, designed two Jewish schools in Vienna. The New World School (1992-94), a kindergarten, is located in mid-town Prater Park. Krischanitz succesfully integrated the school building in its natural setting in various ways, including the orientation of the stepped building volume and a color scheme adapted to the environment, for which artist Helmut Federle was responsible.

Detail of the Holocaust memorial on Frankfurt’s Börneplatz (Bild: Eva K., CC BY NC ND 3.0)

The architects Wandel Hoefer Lorch + Hirsch have focused on Jewish themes. Key projects in this field include the Holocaust memorial on Frankfurt’s Börneplatz (1995) and Gleis 17 (Track 17) at the former Berlin-Grunewald deportation station (1998). The Synagogue and Community Center in Dresden (1997–2001) and the Jewish Center Jakobsplatz in Munich (2001-2006/07) both combine the concepts of Temple and Tabernacle. The Temple symbolizes security and stability, the Tabernacle vulnerability and dispersion.

Avant-Garde

An important aspect in contemporary architecture is the international exchange of ideas. But it is equally remarkable how architecture has given Jewish institutions prominence. This international overview of Jewish architecture hints to an astounding renaissance, comparable only to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in central Europe, or to the United States in the 1950s. One may indeed speak of an “architectural avant-garde” for Jewish projects.

Daniel Libeskind certainly owes his star status thanks to the Berlin Jewish Museum, but other Jewish “star architects” like Richard Meier or Frank O. Gehry neither built in a Jewish style nor for Jewish institutions – interestingly, Meier designed a church for the Vatican, Dio Padre Misericorida (2003). On the other hand, non-Jewish architects such as Mario Botta and William Bruder have built outstanding buildings for Jewish institutions.

Finding

In Berlin the new Jewish Museum was originally conceived as an extension of the Baroque Berlin Museum to house a joint presentation on Jewish and Berlin History (Bild: Studio Daniel Libeskind, Architecture New Building)

The avant-garde projects of Libeskind, Manuel Herz, and Hecker, are prime examples of the architectural idiom of deconstructivism, which appears particularly suited to expressing in concrete terms the discontinuity of history. But there is a variety of contemporary approaches to the construction of Jewish institutions. These buildings all attempt to answer the question as to how to convey Jewish identity architecturally in a cultural and urban context.

Whether in Israel or in the Diaspora, the search for an own identity, for new meaning and spirituality amongst all currents of modern Judaism have become a new challenge for architects, whether in museums, synagogues and schools. At the same time, gentiles identify with this development consciously or unconsciously, since they too are confronted with Diaspora, destruction and a search for meaning – themes Jews are historically familiar with.

Literature

Cohen-Mushlin, Aliza/Thies, Harmen H. (Hg.), Jewish Architecture in Europe, Petersberg 2010.

Sachs, Angeli/Voolen, Edward van (Hg.), Jewish Identity in Contemporary Architecture. Jüdische Identiät in der zeitgenössischen Architektur, München u. a. 2004.

Gruber, Samuel D., American Synagogues. A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community, New York 2003.

Download

Inhalt

LEITARTIKEL: Jewish Architecture!

Edward van Voolen fragt, was Jüdisches Bauen heute ausmacht – von den neuen Synagogen und Museen weltweit schaut er zurück auf die Anfänge der Moderne.

FACHBEITRAG: Erfurts Neue Synagoge

Julius Reinsberg über die einzige moderne DDR-Synagoge – und wie die DDR-Regierung langsam die jüdischen Opfern des Nationalsozialismus vergaß.

FACHBEITRAG: Neues Bauen in Israel

Alexandra Klei weiß, wie die Moderne nach Israel kam: Nicht nur die europäische Avantgarde, sondern auch das mediterrane Umfeld prägten den neuen Stil.

FACHBEITRAG: Helmut Goldschmidt

Ulrich Knufinke zu einem der produktivsten Synagogenbauer der deutschen Nachkriegsmoderne: Godschmidt arbeitete in Dortmund, Köln, Bonn, Münster, …

FACHBEITRAG: Palästina fast-modern

Karin Berkemann zu Missionsdörfern und Orientkulissen im Heiligen Land, das mit dem Ersten Weltkrieg schüchtern zum Sprung in die Moderne ansetzt.

PORTRÄT: Geometry in the Negev Desert

Rudolf Klein rechnet nach, was Zvi Hecker 1970 aus Beton mitten in die Negev-Wüste stellte: die skulpturale Synagoge im israelischen Militär-Lager.

INTERVIEW: Hannover – Kirche wird Synagoge

Die Vorsitzende der jüdischen Gemeinde, die Pastorin der evangelischen Gemeinde und Ulrich Knufinke sprechen über die Gründe und die Folgen der Umnutzung.