by Rudolf Klein (zur deutschen Zusammenfassung) (Heft 15/1)

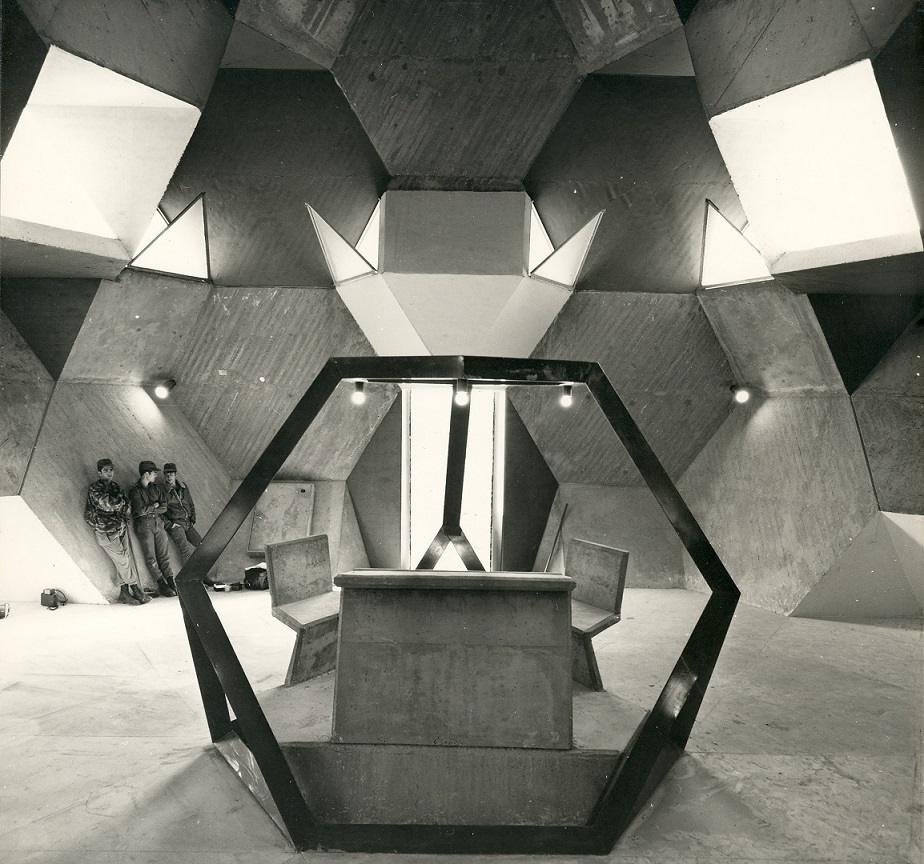

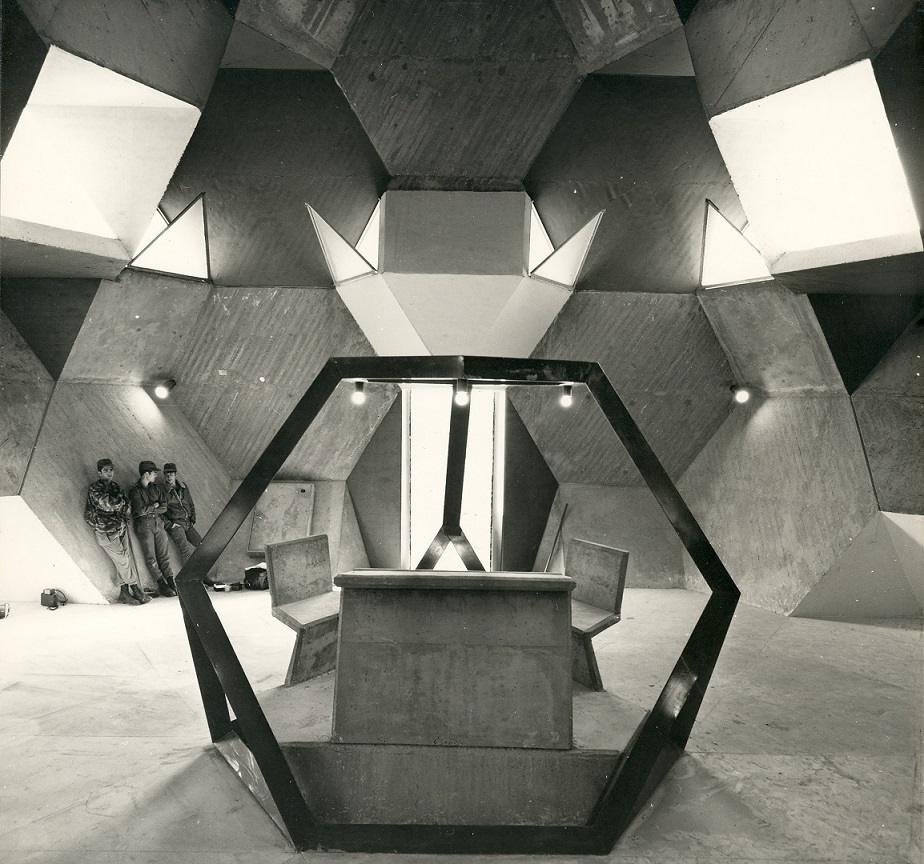

Negev Desert, Synagogue, Zvi Hecker, 1970 (Copyright: Zvi Hecker)

In the new Israeli military camp in the Negev Desert, which consists of four long buildings placed around a central square, the Synagogue (Zvi Hecker, 1969-70) is the most radical implementation of Hecker’s non-orthogonal geometry. This synagogue is set apart from the complex, positioned on its diagonal axis. While the architecture and layout of army buildings express the strict spirit of military life with their orthogonal forms, repetitiveness, the synagogue’s architectural language – forms, colours – contrast the former sharply.

Complex, crystalline, three-dimensional

Negev Desert, Synagogue, Zvi Hecker, 1970 (Copyright: Zvi Hecker)

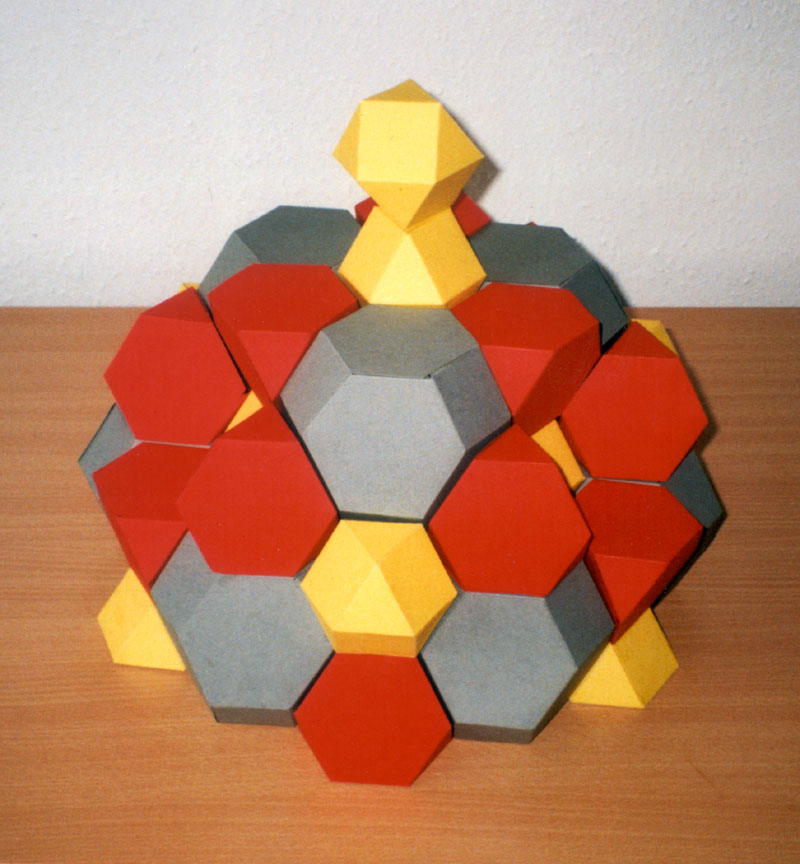

The synagogue with a floor area of approximately 100 m2 seating at least 100 people represents the highest complexity in Zvi Hecker’s early opus in creating space by assembling complex, crystalline, three-dimensional bodies.

Its solitary, multi-faceted volume, surrounded by a desert with sparse vegetation, appears to be without scale because of its precise geometrical shape and absence of conventional openings. The construction consists of the combination of three spatial geometrical cells: the octahedron, the tetrahedron and the cuboctahedron. The three solid elements make up a truncated octahedron. The union is not fortuitous, but it seems rather to be the result of successive germinations emanating from a central pole.

Centrally orientated, two spatial foci

Negev Desert, Synagogue, Zvi Hecker , 1970 (Copyright: Moshe Gross)

The plan is centrally orientated, but reflects the double focus arrangement of traditional synagogues – with two important poles: the Bimah, an elevated central platform, for the reading the Torah, and the Ark, at the eastern end, consisting of a niche, which houses the Torah Scrolls, accessible by means of a ramp. The entrance is placed on the same axis that points towards Jerusalem. Seats for the worshippers are placed along the sides of the axis, and they are inclined so that both the Bimah and the Ark can be seen simultaneously.

Two thirds of the total volume represent the synagogue, the remaining third is underground and contains a water reservoir which supplies the whole military camp. The space of the synagogue, divided into horizontal sections at different levels, varies and progressively narrows down towards the top. The central symmetry has been kept, however maintaining the importance of the two spatial foci throughout.

With warm yellow light

Negev Desert, Synagogue, Zvi Hecker, 1970 (Copyright: Zvi Hecker)

A special skylight supplies the interior with warm yellow light; it consists of two superimposed cuboctahedrons, with one side in common. Light and air penetrate through the triangular facets of the upper cuboctahedron and they then enter the synagogue from the top through the facets of the lower cuboctahedron. Light is also admitted through other openings in the enclosing surface. These are triangular facets of component volumes, which are left open. Consequently the light never penetrates directly into the interior but skims over the geometrical facets from which it is reflected.

The structure is cast in-situ concrete, 14 cm thick, except of the roofing, where due to inclination changes were needed for draining Water. Shuttering was manufactured in a manner that highlighted the timber’s imprint on the concrete, in- and outside alike.

The spatial search of Zvi Hecker

Bat Yam, Town Hall, Zvi Hecker, 1969 (Image: Ori~, PD)

The synagogue is a further manifestation of the spatial research to be found in the Town Hall of Bat Yam (Zvi Hecker, 1969) and in Dubiner House (Zvi Hecker, 1964). The geometrical patterns of the octahedron are already evident in the Town Hall, but there it is more a decorative element, repeated and emphasized at all its possible configurations within an already organized space.

In Dubiner house space consists of the combination of geometrical modules. However, while there the combination of the cells is limited to the floor plan and the elevation maintains the traditional vertical direction – though with some dislocations –, in the synagogue the entire space is made up of geometrical modules differing in all three dimensions.

The abstraction of the geometrical theme

Academic project to calculate and build a paper model of Zvi Hecker’s Synagogue – a plan can be downloaded (Copyright: Institut für Mathematik und Informatik, Universität Greifswald)

In the synagogue it is not so much the component module but the total resulting volume, which is important in the combination of the geometrical cells. Rossella Foschi emphasises that “the prominence, the author wants to give to the process of the geometrical composition is not clear, so much so that he paints the outside of the geometrical solids forming the total volume in different colours (green, yellow and natural concrete).”

After thirty years has elapsed, we do not ask for such principles any more, but appreciate more the integrity of artistic creation. Zvi Hecker’s abstraction of this geometrical theme refers to some earlier spaces of 19th and early 20th century synagogues that tried to depart from the orthogonal scheme in order to adopt the place of Jewish worship to its ancient symbol, the star of David and its cosmological meanings. But in this case, geometry is carried further into a real three dimensional pattern.

Galery

A small selection of the work of Zvi Hecker …

Negev, Synagogue, 1970 (Copyright: Zvi Hecker)

Negev, Synagogue, 1970 (Copyright: Zvi Hecker)

Negev, Synagogue, 1970 (Copyright: Moshe Gross)

Negev, Synagogue, 1970 (Copyright: Moshe Gross)

Jerusalem, Ramot Polin, 1975 (Image: Nehemia G)

Ramad Gan, Spiralhouse, 1989 (Image: Aviad2001)

Tel Aviv, Palmach Museum, 1996 (Image: Ori~)

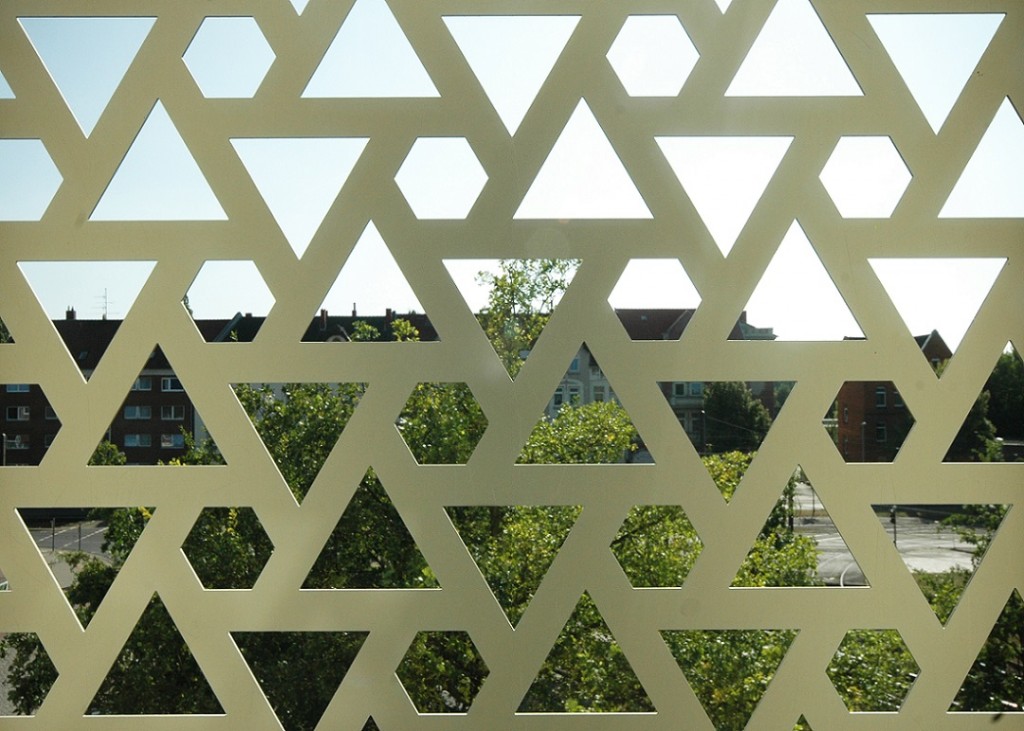

Duisburg, Jewish Community Center, 1999 (Image: Nomo)

Literature

Klein, Rudolf, Zvi Hecker – Oltre il riconoscibile, Torino 2004.

Foschi, Rossella, Una Sinagoga nel deserto del Negev, in: L’Industria Italiana del Cemento 1981, 12, p. 963-972.

Download

Inhalt

LEITARTIKEL: Jewish Architecture!

Edward van Voolen fragt, was Jüdisches Bauen heute ausmacht – von den neuen Synagogen und Museen weltweit schaut er zurück auf die Anfänge der Moderne.

FACHBEITRAG: Erfurts Neue Synagoge

Julius Reinsberg über die einzige moderne DDR-Synagoge – und wie die DDR-Regierung langsam die jüdischen Opfern des Nationalsozialismus vergaß.

FACHBEITRAG: Neues Bauen in Israel

Alexandra Klei weiß, wie die Moderne nach Israel kam: Nicht nur die europäische Avantgarde, sondern auch das mediterrane Umfeld prägten den neuen Stil.

FACHBEITRAG: Helmut Goldschmidt

Ulrich Knufinke zu einem der produktivsten Synagogenbauer der deutschen Nachkriegsmoderne: Godschmidt arbeitete in Dortmund, Köln, Bonn, Münster, …

FACHBEITRAG: Palästina fast-modern

Karin Berkemann zu Missionsdörfern und Orientkulissen im Heiligen Land, das mit dem Ersten Weltkrieg schüchtern zum Sprung in die Moderne ansetzt.

PORTRÄT: Geometry in the Negev Desert

Rudolf Klein rechnet nach, was Zvi Hecker 1970 aus Beton mitten in die Negev-Wüste stellte: die skulpturale Synagoge im israelischen Militär-Lager.

INTERVIEW: Hannover – Kirche wird Synagoge

Die Vorsitzende der jüdischen Gemeinde, die Pastorin der evangelischen Gemeinde und Ulrich Knufinke sprechen über die Gründe und die Folgen der Umnutzung.