by Jonathan Palmer-Hoffman (24/1) >> deutsche Übersetztung

No tower exemplifies the technological, political and social progress and turmoil of the 20th century more than the teletower. While the first broadcast tower emerged in the late 19th century first as a radio antennae – it would quickly find a host in the World’s Fair Eiffel Tower and the basic typology of the broadcast tower emerged – the transmitter as icon. The early twentieth century saw innovative iron and steel towers built, however it was in the 1950s that the first teletower would be constructed.

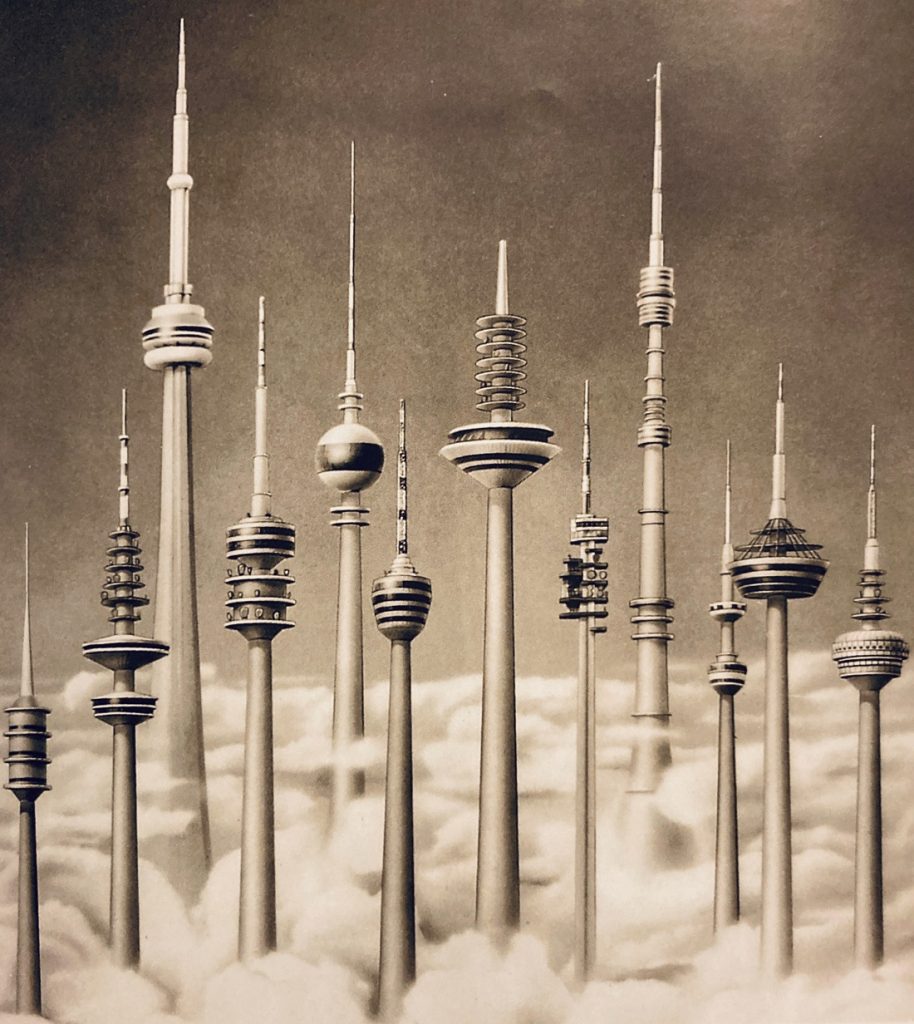

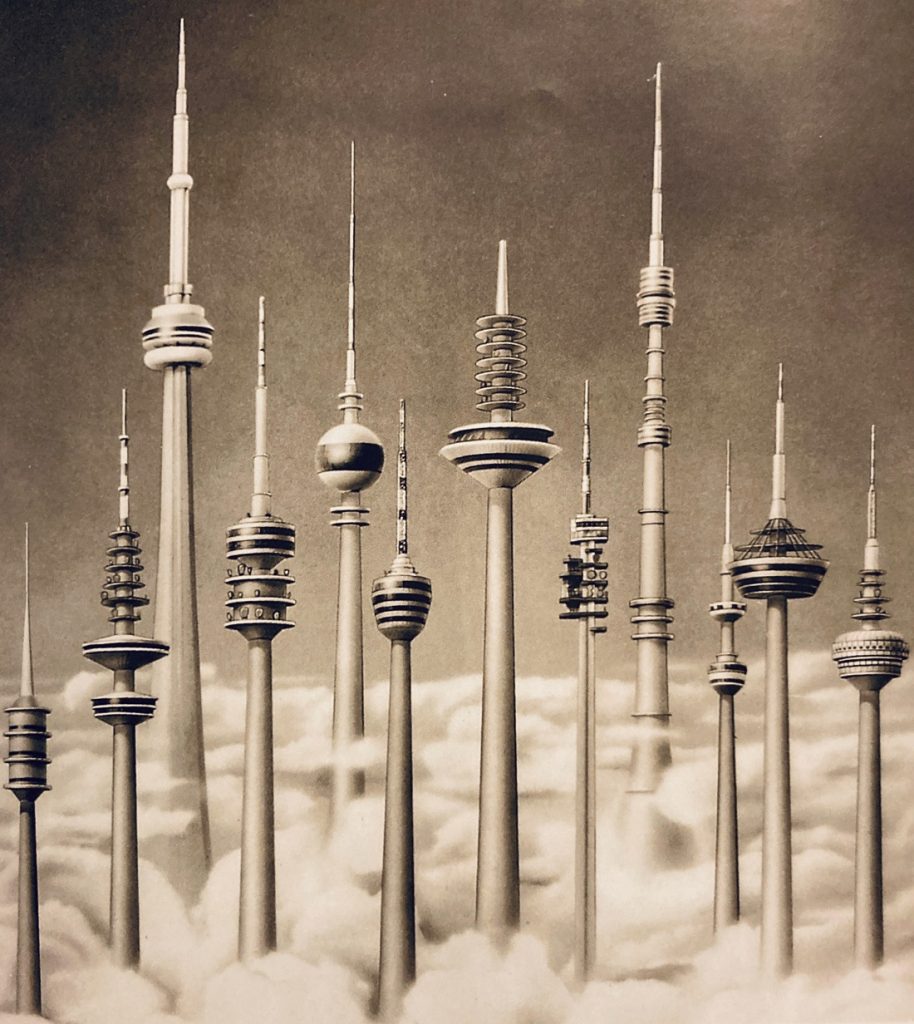

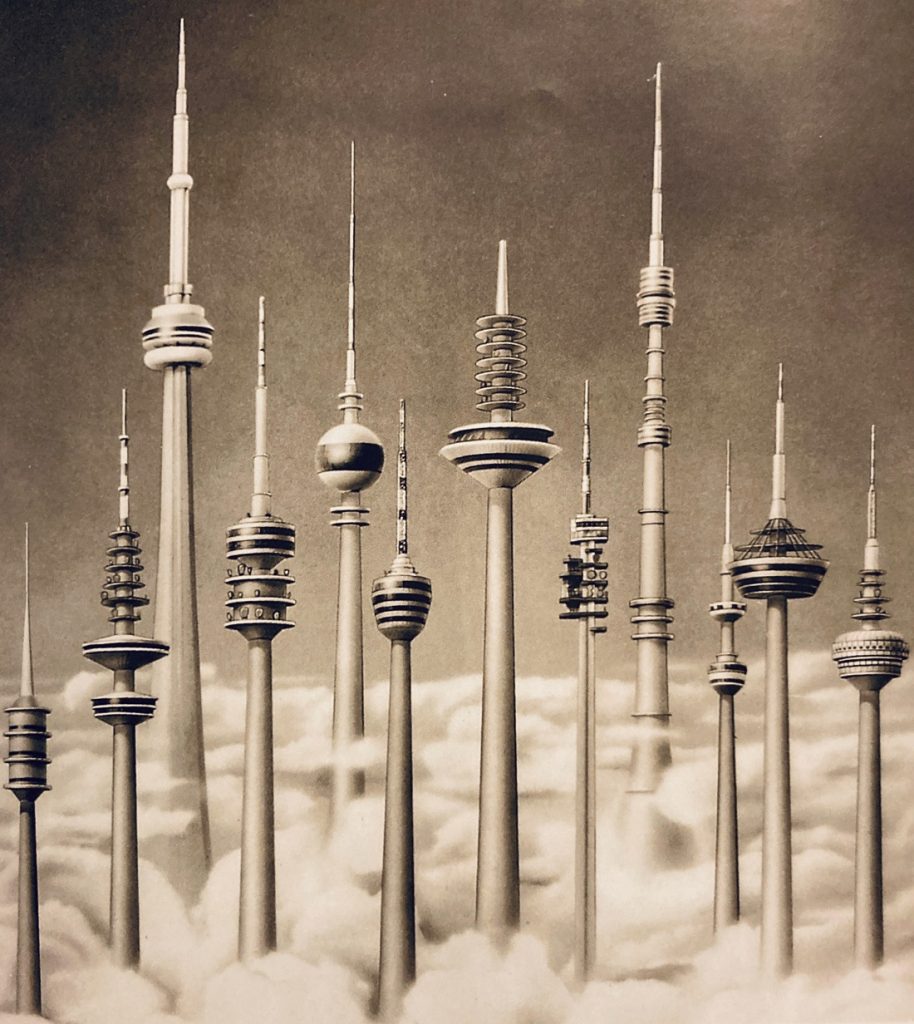

Teletowers, advertising graphic by Bosch, 1968 (photo: historical advertising)

Teletowers

Teletowers, borrowing a term coined by curators Jane Pavitt and David Crowley for the 2008 Victoria Albert Museum exhibition “Cold War Modern”, are defined here as transmittal towers (for radio, television, etc) combined with visitor facilities (viewing platforms, restaurants) or the implied accommodation of such facilities. The teletower is typically built of reinforced concrete, although notable exceptions exist. The teletower’s irrefutable origins can be traced to Cold War partitioned Germany, where aesthetic and typological forms would be established that would spread, regardless of political or ideological boundaries.

Stuttgart

Completed in 1956, the Stuttgart television tower was built of reinforced concrete and contained an observation platform and restaurant. Designed by architect Erwin Heinle and engineer Fritz Leonhardt, Stuttgart is pivotal as the first teletower typology. Notably, the original design was changed to a concrete tower at the persuasion of Leonhardt, as “a steel grating mast would not have fit well into the beautiful landscape.”

After the completion of Stuttgart, Heinle and Leonhardt immediately went to work on a shorter but distinctive tower for the German Industrial Fair in Hannover. Less focused on broadcasting and more a tourist attraction, the structure featured two columns and an external elevator, which would prove oddly prescient for other towers to come. At the same time, a development in directional wireless transmission necessitated large, parabolic mirrors to be perched on the outside of new towers to accommodate microwave radiation. Though this innovation would render Stuttgart limited to local radio and television, newer teletowers would be designed to accommodate the required dishes.

Moscow, Ostinako Tower, 1964 (photo: mos.ru, CC BY SA 4.0); Stuttgart, teletower (photo: Julian Herzog, CC BY SA 3.0, 2013)

Go East

The duo would go on to design many teletowers throughout Western Germany, but what is quite interesting is that a little over a decade after the completion of the inaugural tower in Stuttgart, Leonhardt would consult on what would become the tallest teletower and first free-standing structure to eclipse the Empire State Building – the Ostankino Tower in Moscow. How a Western German engineer ended up working on a Soviet tower is another question, but what is indisputable is that this collaboration resulted in an exacerbation of the forms set in Stuttgart to create a more cosmic tower form, through its rocket ship manifestation.

Back in Germany, Einle and Leonhardt kept busy in the 1960s, designing or consulting on towers in Hamburg and (again over the Iron Curtain) in East Berlin. These towers again showed an extraordinary evolution of the tower pulpit, departing from Stuttgart’s crow’s nest to a series of stacked rings in Hamburg and a giant, faceted sphere in Berlin.

Typical

Concurrently, the duo would have a hand in the standardized concrete “typenturm” that would spread throughout West Germany – telecommunications towers commissioned by the West German Post Office with no planned visitor accommodations that proliferated across the country as growing signal networks demanded. In contrast with the aforementioned “sonderturm” or special towers designed for a specific location, i. e. to be a city’s landmark, the typical towers followed a basic template and would be built atop mountains, in forests, and outside cities in a pattern that would continue beyond reunification in the early 1990s.

East Berlin, teletower (photo: Jonathan Palmer-Hoffman); Nuremberg, teletower (photo: Wladyslaw, CC BY 3.0)

Egg

The 1970s would see the duo jump across the Atlantic Ocean to consult on the CN tower in Toronto, which would strip Moscow of its tallest title and also feature exterior elevators. Back in Germany, the architect and engineer designed teletowers for Kiel, Mannheim, Koblenz and Frankfurt. While these forms displayed an interesting evolution in the tower typology since Stuttgart, 1980 would see a stunning departure in Nuremberg, with an ovoid structure commemorating “Peter Heinlin’s egg-shaped pocket watch”.

In Nuremberg, the original design intent called for the entire tower pulpit to be encased in a permeable plastic shell, and although this was partially omitted, the tapering disc platforms still achieve the egg shape. Reflecting on this teletower, it is interesting to note Leonhard’s own words on his designs: “…the tower shape derived entirely from rational considerations, typical for engineers, as to how the task could be fulfilled with a minimum of expense.” As we can see, this was anything but!

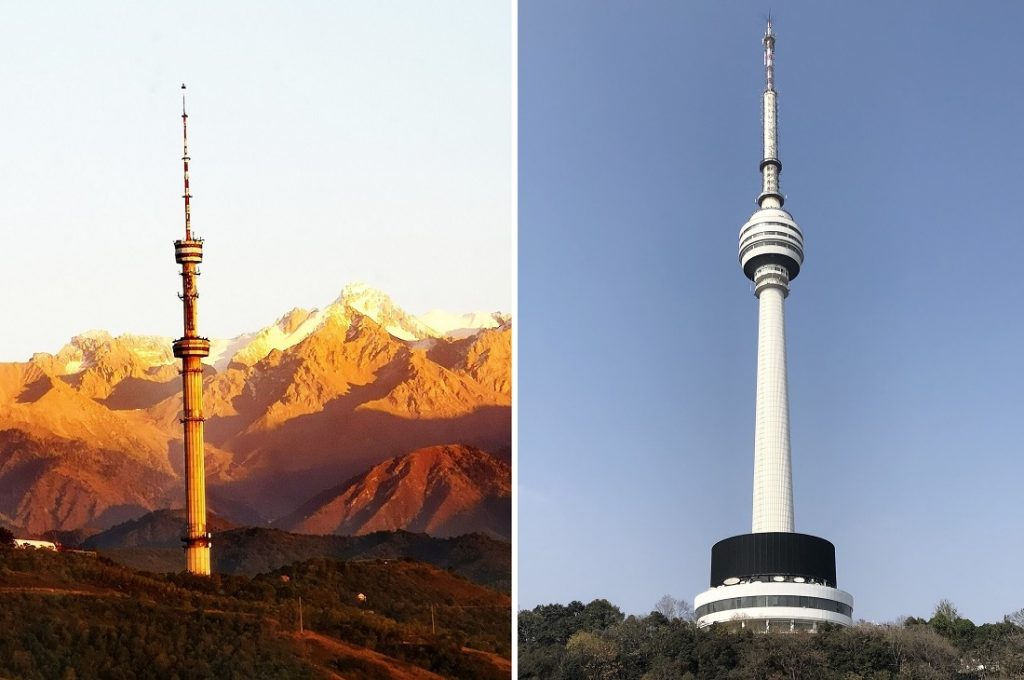

Almaty Tower/Kazakhstan (photo: Gulim 8, CC BY SA 4.0, 2019); Guishan Tower/China (photo: 汮汐, CC BY SA 4.0, 2020)

Go Further East

The 1980s would see the pair in the Soviet Union again, as both Heinle and Leonhardt would contribute to the design of the Almaty Tower in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, completed in 1982. A teletower in name only, the structure is not only closed to the public but also constructed from steel and coated in metal plates to give the appearance of concrete. While originally rejected in the Stuttgart design, steel would reappear as the material of choice in Central Asia. Finally, the architect and engineer would go even further east to consult on an early Chinese teletower – the Guishan Tower in Wuhan, completed in 1986. This is a nearly identical replica of the first Stuttgart tower, but taller. This would kickstart a tower mania in the country, as nearly every big Chinese city would construct a signature landmark in the economic boom.

Back in Germany, a preponderance of teletowers accumulated across both West and East Germany and would continue after reunification. Many of these would be the typenturm based on Heinle and Leonhardt’s template, but quite a few sonderturm would emerge in the D-A-CH region which displayed champagne-fluted, asymmetrically-stacked, dramatically-cantilevered and parabolic-shafted teletower forms. Yet at their root, all of these teletowers, across the region, Europe and indeed the world owed their diverse forms to the first successful towers to combine telecommunications with visitor amenities, designed by Erwin Heinle and Fritz Leonhardt.

Brackenheim, “Typenturm” (photo: Zonk43, CC BY SA 4.0); Toronto, CN Tower (photo: Maksim Sokolov, CC BY SA 4.0)

References

Böttger, Matthias/Heilmeyer, Florian/Borriers, Friedrich von (eds.), TV Towers. 8,559 Meters Politics and Architecture, Berlin 2010.

Crowley, David/Pavitt, Jane (eds.), Cold War Modern. Design 1945-1970, London 2008.

Heinle, Erwin/Leonhardt, Fritz, Towers. A Historical Survey, New York 1989 (from this also the quotes in the article above).

Janberg, Nicolas, Television transmission towers, in: Structurae.

Pahl, Burkhard, Technische Türme, in: Indumap.

Download

Bonusbeitrag

Inhalt

Der Bedeutungsüberschuss

Sonja Broy über Türme als symbolische Orte und ihre Rolle in der modernen Stadt.

Die Väter der Fernsehtürme

Jonathan Palmer-Hoffman über die Fernsehturm-Prototypen von Erwin Heinle und Fritz Leonhardt.

Fathers of the Teletowers (English Version)

Jonathan Palmer-Hoffman on the prototypes of the teletowers by Erwin Heinle and Fritz Leonhardt.

Ein Wasserturm als Mahnmal

Klemens Czurda über den Wasserturm von Vukovar, der eine neue Nutzung fand.

Der Zementriese

Robinson Michel über das Wiesbadener Dyckerhoff-Hochhaus, das sich selbst als Werbeträger der Baustoffindustrie präsentierte.

Eine Rotationshyperboloidkonstruktion

Martin Hahn über das mathematische Prinzip hinter dem Möglinger Wasserturm und was das Ganze mit Moskau zu tun hat.

Der Naturzugkühler

Haiko Hebig über Landmarken einer vergangenen Energiepolitik.